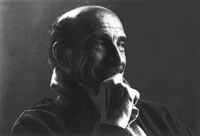

EDOUARD BOUBAT

Edouard Boubat

Photograph Frank Horvat

Born in Paris, September 13, 1923.

Studies in typography and design at l'École Estienne.

Photographer since 1946.

Staff photographer for Réalité beginning 1951.

Independent photographer beginning 1968.

Documentary reporting in numerous countries, usually in black and white.

Deceased 1999, in Paris.“I think that the photos that we like were made when the photographer knew how to disappear.If there were a secret, certainly that would be it.”

Frank Horvat : At first I wanted to call this book “The art of not pressing the button.” People persuaded me against it, saying it wouldn’t be commercial, a negative statement wouldn’t sell. On the other hand, what is more appropriate to photography than the negative? You may say: “Why not the positive?” You like to be positive, I know, you love people, voyages, life, you love to say that you love those things, and your photos certainly reflect that outlook. I am positive, too, in my own way, but I function differently. I like to define things by what they are not. Rilke, in one of his Elegies, says that we only know a feeling by its outline. It seems to me that we could help people better to understand photography, by saying what it is not, by defining what we refuse. Besides, the etymological meaning of “define” is: “drawing the limit”.

Edouard Boubat : You are right in saying this. To me, photography is like a quest, or a pilgrimage, or a hunt. I love painting, I love music, but photography is what has allowed me to get outside of myself. If I were eighteen years old, I would take up drawing, if I were four years old, I would study music. But if I were seventy-five, I would continue to photograph.

Frank Horvat : You say hunting. Doisneau says fishing, and it’s very true for him. One could also say that photography is like sculpture – I mean sculpture in marble or in wood, where the shape doesn’t come from what the sculptor adds, but from what he takes away: a process of subtraction, of sorts.

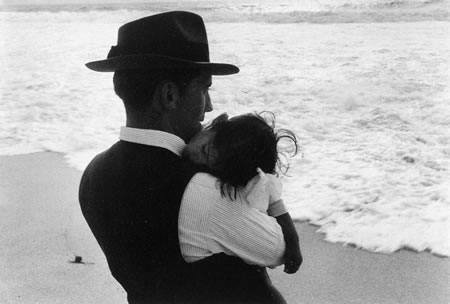

Edouard Boubat : Yes, in a photo there are always too many things, except when it’s a good photo. To speak specifically of my own work – because that’s what we are here for – I believe that, from the very beginning, I managed to make photos where there was nothing more than what was needed. Take the little girl draped in dried leaves, where everything else is but a blur. It was just after the war, all it shows is that little girl. Click. Or the man with the baby, by the seaside. Nothing but him. Click.

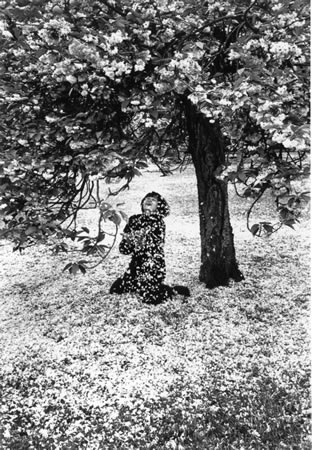

Photo Edouard Boubat

Frank Horvat : Yes, we are here to talk about your work, but also to try to define photography in general – or at least to clarify our ideas about it.

Edouard Boubat : On the other hand, we know that there isn’t just one kind of photography, as there isn’t just one kind of music.

Frank Horvat : Of course. One could even say that every important photographer invents his own form. Every great artist broadens the territory of his art. Picasso made works which, before him, wouldn’t have been accepted as painting.

Edouard Boubat : Even though, in another way, and at the same time, the territory shrinks. What Robert Frank, Eugene Smith, Cartier-Bresson did, they could no longer do. Or Doisneau. His Paris no longer exists, he could never again find that atmosphere of the 50s. I was told that the same tennis player, photographed in New York, Berlin or Paris, wouldn’t “give” the same photo, because the atmosphere wouldn’t be the same…. Atmosphere is nothing, and at the same time it’s a lot. One notices it when looking at a movie from fifty years ago. This is one thing that a photo can catch, sometimes without intending to.

Frank Horvat : I would like to come back to the “refusal”. When you say “searching”, you mean traveling, walking around, investigating. But your search also involves refusing, deciding that this is not the place you were looking for, not the right angle, not the right choice on a contact sheet, not the right way to make the print. It is this series of refusals which shapes your work, just as a sculpture is shaped by the marble that is removed.

Edouard Boubat : I follow you. Millions of unnecessary photos are taken every day. People stand before the Pyramids and photograph them, when for three cents they could buy post cards which show them much better.

Frank Horvat : And as they purchase improved cameras, with more motor-drives, zooms and automated gadgets, they keep clicking more and more, as if to say: “let’s shoot first and see later. There was that American, Winogrand, who said, "I photograph to see how it will look in a photo.” A phrase that always bothered me, even though, thinking about it, I ended by understanding what he meant. But I come back to my question: does photographing, for you as for me, imply some kind of refusal? Do you know what you refuse? Could you describe it?

Edouard Boubat : I know that one doesn’t get more than two or three good photos a year. But there are some blessed moments. I remember a superb morning, in Brazil: I arrive at an old circus, and I know right away that I have to take photos, that something there is being given to me. Of course I took some other photos during the rest of that trip, but without really believing in them, it wouldn’t even have been worthwhile developing the rolls, I knew I would never blow them up. There are days when one walks around without getting a single photograph, without running into anything. There I refuse. But there are other times when things are offered to me, like gifts. I arrive, I stroll around town, everything is given. Click. It’s like the story of the magic gift, which comes up in many teachings, for instance by the Sufis, but also in some of our own legends. But in order to seize that gift, one has to be prepared. If I am, and if my camera is there at the right moment, click, all I have to do is accept it.

Frank Horvat : You know that these gifts can be given to you, even if they are not always given when you need them, and not necessarily because of your efforts – otherwise you wouldn’t call them gifts. Nonetheless, they are destined to you, personally, which means that you have deserved them, in some way, perhaps by some gestures or by some actions, by something that you did or that you avoided doing – and which improved your chances. Some kind of magic acts. Could you define these acts, or at least situate them?

Edouard Boubat : You know, in photography we use some marvelous words, like “aperture.” One is the camera’s diaphragm, which is a mechanical thing, but there is also our own “aperture”, our own opening up to reality. Take the photo of the man on the seashore. It was my first trip to Portugal, I believe it was in 1956. In those days traveling seemed extraordinary, there were very few tourists, we had been on the road for two or three days, we arrived at a hotel by the seaside, Sophie was a little tired, and I said, “I am going to the beach,” I had only my little old Leica, and that man was there, click. I had only arrived half an hour before, but there he was, with his child, as if he had been waiting for me, and so I took my first photo of Portugal, a photo that will endure. I had come a long way, I had dreamt of Portugal, so in a sense I too was waiting for him, there was expectation on both sides. In some way, a photo is like a stolen kiss. In fact a kiss is always stolen, even if the woman is consenting. With a photograph it’s the same: always stolen, and still slightly consenting.

Photo Edouard Boubat

Frank Horvat : I’ll buy that. But I shall continue hammering at my point, by asking the same question in another way: when eventually you got your kiss, isn’t it as if there had been a discharge? As if some time had to pass before you could get the next one?

Edouard Boubat : There is what they call “le coup de foudre”, a superb word, untranslatable, “thunderstruck” would be the closest. When I arrived in China for the first time – we had traveled by train, Sophie and I – the train arrives in Peking, click, we get off, we leave the station, there are no taxis, but the hotel is close by, ten minutes on foot. Well, within that quarter of an hour, I have seen all of China. That doesn’t mean that I couldn’t return there ten times and see it each time in a different way. But it means that from that first moment I’d seen everything, felt everything. Remember when arriving in India, in Calcutta, for example, the road from the airport to the hotel: it’s the whole of India. And that hotel in Calcutta, the guy with the stick who keeps away the beggars, and all the people lying on the pavement: the whole of India. Or New York. Between Kennedy Airport and Manhattan, you have seen all of America, you have smelled its scent. And it’s the same with portraits. Those first contacts are what I love most. There is always an urge, when photographing, that goes beyond mere intellectual curiosity. Click. Thunderstruck. But I did hear your question: can it be repeated? I believe it can, at least on some occasions.

Frank Horvat : But don’t you have the feeling that when that kiss has been exchanged, there is something that is drained, as if the batteries had to be reloaded?

Edouard Boubat : Absolutely. That spark, that strike of lightening, is something that we can only obtain from time to time, even if we refuse other things, which we know to be of less value.

Frank Horvat : So how did you spend your following days – for instance in Calcutta? Did you try to recall the feeling of those first fifteen minutes?

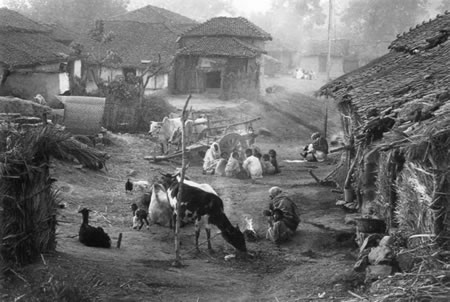

Edouard Boubat : My assignment was to cover the life of a man living in the street – as you know, about one third of the people in that city live and sleep on the pavement. What I remember best are the mornings, that is something else I would like to talk to you about, even if it doesn’t exactly answer your question. But I am doing it on purpose, just to annoy you a little. I would like to speak of those mornings. Click. I remember people still asleep, like corpses in shrouds, in fact some were actual corpses, in actual shrouds. Those mornings with that fabulous light – I always loved that light. Or the mornings in New York, we haven’t been there together, but we certainly lived the same thing: one goes out to have breakfast, the sky is blue, when you leave the coffee shop, the fellow behind the counter says: “Take care” (English in the original), it’s just a wonderful thing. Or that other morning, when I woke up in an Indian village, the previous evening the people had welcomed me, saying: “You may sleep here.” So I really slept there, on the ground, there wasn’t anything else, I got up very early – when you sleep on the ground you get up early – and I made that photo of the village, with those hens, that cow, in that foggy light. And on that occasion, to come back to your question, there was nothing to be refused, the photo was in front of me. Click. I only shot two or three, there was no reason to take fifty. In those rare moments, when there is nothing to be refused, one doesn’t have to shoot ten rolls, the photo is there. Click.

Photo Edouard Boubat

Frank Horvat : Yes, awareness is an essential point. If I had to describe you to someone who knew nothing about you, I would say, “Boubat looks at the world as if he had just landed and as if his eyes had just opened.” Perhaps what you search for, most of all, are those moments when your eyes open. As Goethe said, in a phrase that you often cite, “The most difficult thing is the one that seems the easiest: truly to see what is in front of our eyes.” The magical act would be to know how to keep that state of awareness.

Edouard Boubat : Every moment has to be lived as unforeseeable. I had the luck to meet Eugene Smith, who for me was one of the greatest photographers ever. I met him in 1950, and already by that time he had many problems with Life, because they kept telling him – him, the greatest of their photographers – “You have to photograph this, to do that…” And he, who was a hypersensitive person, was sick of it, because he knew only too well that one couldn’t predict what one was going to find. I also remember a guy, in Africa, who was walking behind me – or ahead of me, I hardly remember – in a kind of forest, and saying to me, “It’s not a matter of looking, it’s a matter of seeing.” I didn’t understand right away, but I thought about it. I think he meant that one shouldn’t care too much about details, but rather see the whole. In those blessed moments that we spoke about, I see nothing, I am taken in by a whole. Of course I see well enough to frame my picture, click. But when I look at a face, I’m not concerned with details, I don’t know if the guy has pimples. I am moved by the whole – that’s what I mean by being aware.

Frank Horvat : People tell me that I have very little sense of observation, my wife really finds it strange for a photographer. Could it be because I perceive the whole rather than the details?

Edouard Boubat : It’s exactly what that African meant. Then again, Goethe, whom you just mentioned, also said that the whole and the details should be seen at once. I find it extraordinary, that some people should be able to do that. It reminds me of some painters, where the foreground and the background blend into a whole. You notice it with Bonnard, but also with painters of the Renaissance: everything is blended, but each object has its importance. Still, I believe that the “coup de foudre” is generated by the whole. But then again – and this is where photography is really amusing – you may look at a press photo, no matter which one, let’s say of the Queen of England, and find that what’s most interesting is not so much the queen, but some small detail, like a horse that’s not where it should be, or some other tiny thing. Whether he wishes it or not, the photographer reveals things which he himself had not seen at that moment, but which inform us about that country and that era. In a photo there can be ten thousand more things than he wanted to show. He believes that he only shows the small visible part of the iceberg, but his photo may also reveal what is beneath the surface.

Frank Horvat : : I would like to find out more about your secrets. I know that you have often been invited to teach at schools or seminars, and that you have always turned it down, explaining that a photo-journalist’s work cannot be taught. But if someone came to ask you the real questions, not: “which camera, which lens, which aperture?” but: “Mr. Boubat, what is your magic formula for obtaining those gifts?” – would you have any answers? Are there things that you eat, or that you don’t eat, things that you do before going to sleep, or that you don’t do, thoughts on which you concentrate or others that you avoid? Like that Californian, Minor White, who recommended time for meditation before picking up the camera. That always made me smile, I am not Californian. However, I sometimes think that he was not entirely wrong. But what are your own secrets?

Edouard Boubat : I am very much like you: when I get interested in music, or in those spiritual things, I would like to know “the secret”. But in fact there is no general rule, each person must find out for himself. We are all different – and some of us are more gifted than others. My own formula is the “coup de foudre”, the global view. Perhaps because I am unaware of details, just like you. Sometimes, at a party, I don’t even recognize people, which often makes me seem impolite…. Or, as another secret, I could tell you a little story that may seem beside the point, but that to me is meaningful. One of my first reportages, for Réalités, was about the “Hospice de Beaune”. I had the luck to see it while it was still in operation. That hospice was built by a mean man, who had three or four wives at a time, and children all over the place, so his bishop said to him: “To redeem yourself, you have to build something.” As a result he built that hospice, in which everything is beautiful, not only the architecture, but even the glasses that one drinks from. He hired a Flemishman – in those days there were no photographers – and commissioned him to paint a triptych, which is still to be seen. But it is not simply an object for your eyes: it used to be opened from time to time, I believe once a week, and all the sick people would come and, just by looking at it, already be half cured. When I take a photo, it’s a little like that, I wish people to feel better by just looking at them. “To be cured” may be too strong a word, but why not? Borges wrote: “Every man who reads Shakespeare is Shakespeare.” When you hear Mozart, you are Mozart. I recall some letters by Mozart, saying: “The only tolerable moments in my life are when I compose.” He had debts, he didn’t have enough to eat, but when he was composing he was more than Mozart, he was in another state. If you wish, that is my secret.

Frank Horvat : This reminds me of some people telling me, “I don’t look at trees in the same way since seeing your photos of trees.”

Edouard Boubat : That was your reason for making them. Though I must say that for me, the most beautiful part of photography is the moment of shooting, the moment when I make a portrait, or a landscape, Then Boubat no longer exists. That’s the secret: there is no Boubat any more, no Indian village, in that briefest of moments we become part of a whole, we are no longer separate from the landscape, from the person in front of us. That’s why I don’t notice the details: because there are no details any more, I don’t see them – while at the time same time I see well enough to frame, to know that if I move a little to the left or to the right, the photo may be gone. In that blessed moment, there is no Boubat any longer, nor anything else.

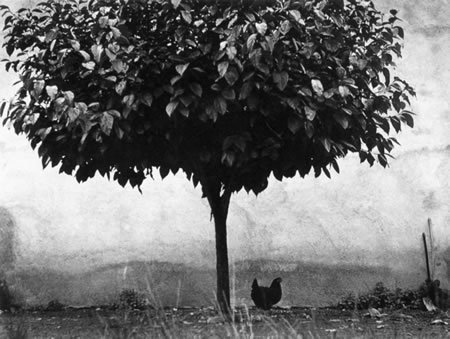

Frank Horvat : But why did you choose that particular image of the hen and the tree, rather than the thirty-five other ones on your contact sheet?

Edouard Boubat : In fact, there were no thirty-five others. That photo has a story. Thanks to Eugene Smith, I had been sent to the South of France – I didn’t have a penny at the time – to do a story on corn. I was using a Rollei – and in a Rollei, you recall, there are twelve pictures. I had finished covering the story, I was going to take a train at six in the evening, it was four o'clock, there was one last photo left in the camera. I pass a yard on the farm, I see my tree with the hen, click, I take the photo, it was simply to finish my roll. There is only one photo of the hen and the tree, it was picture number 12.

Photo Edouard Boubat

Frank Horvat : But what is the difference between this photo and all the others that you made during the trip?

Edouard Boubat : I think that the photos that we like were made when the photographer knew how to disappear. It is when people like Lartigue, Doisneau, Cartier-Bresson knew how to disappear, that their photos became the Lartigues, the Doisneaus, the Cartier-Bressons. But it takes nerve for that, because everything, in our time, pushes us into the opposite direction, everything we see, everything the media make us believe. Nowadays, photographers start out with ideas, and their photos become the expression of an idea. To my way of thinking, a photo should not depend on ideas, should go beyond ideas.

Frank Horvat : You say “disappear,” and I can agree with that. But for me there is another key word, which means almost the opposite: “face up.” For me, to photograph is to face up to something. My “gift-moments” come when, one way or the other, I have to face up. That’s what I often say to young people, who show me their photos of shadows on walls or torn posters, more or less manipulated in the darkroom. “It’s interesting,” I say “but you haven’t faced up to anything.” In my case, before any important photo, I get stage fright, even more so at my present age than when I was less experienced, and in spite of working with a light that I know well, in a studio that I had built to my specifications, with assistants, stylists, make-up artists, hair dressers, who are all there to help me. I may rehearse before shooting, I may shoot fifteen rolls on a subject – but I still get stage fright

Edouard Boubat : What can you be scared of? You don’t often make technical mistakes!

Frank Horvat : I am scared of facing up, of missing the decisive moment. It’s the fright of an actor before each performance, even if he has played that role hundreds of times.

Edouard Boubat : On the other hand, when I say “I disappear”, I also mean that I let Boubat come out even more. That’s what must be made clear: because Boubat cannot be reduced to “just Boubat,” even though most people are unable to understand this. There is another very beautiful line of Borges, “A writer, who only puts what he intends into his novels, is a very poor writer.” In each photo there are ten thousand more things than we intend to put into them. Like atmosphere. To disappear is an act of humility, for sure, but it’s also an act of cleverness, I would almost say of slyness. That’s what it is! Unless we disappear, we can only show poor Boubat, or poor Horvat. But we don’t want to be reduced to a mere Boubat or a mere Horvat or a mere Eugene Smith or a mere whomever!

Frank Horvat : But don’t you ever get stage-fright? Don’t you ever make mistakes? It could be interesting to talk about our mistakes, it’s a little like talking about refusals.

Edouard Boubat : I don’t know if they were real mistakes. Sometimes I envy painters, it is wonderful to remain in front of a bouquet of flowers a whole morning, or even longer. A photographer is like a cloud, pushed all around, always dependent on the exterior world. That’s what I sometimes feel as a pain and an error. I would prefer things to depend more on me – all the while knowing that my dependence is also my chance.

Frank Horvat : Edouard, you are like a snake, you slither away from the subject each time that I try to corner you.

Edouard Boubat : You say that I escape: but we are speaking of things that are difficult to express. There is a little dilemma that we all face, because we now use those 35mm cameras. Atget only made one or two plates, and each time it was an Atget. There you had a man who knew how to disappear! Our own drama, with these little 35mm cameras, is that we shoot too much. If we truly were strong, we would only make three or four exposures. Of the tree and hen, I only made one; of the little girl in the leaves, only one; of Leila on the boat, only one. The subject gets used up. Now, even Paris is used up. Luxembourg Gardens are used up, there are too many cameras around. But I would like to come back to what seems to me the most important, the search. We see the sufferings of the world, the poor, the less poor, we are there, with our tongues hanging out, in eagerness to know what’s going on behind all that. That’s perhaps why photographers live to be old. Like Kertesz or Brassaï or Lartigue. I met Cartier-Bresson the other day, he was like a young man, on his feet and photographing for an hour. Ultimately, the photographer is the guy who hasn’t found anything, but goes on hoping, until the very last moment. That’s what drives him, what keeps him on the run. You asked me where I was going this afternoon. I’ll go to the lab, I don’t have any photos to take, but nonetheless I’ll cross the Seine on foot, by one the bridges. I’ll take along my little amateur Leica, not quite a camera to make real photos, but still I may get one, who knows? I walk into the unknown, you see? Photographers stay young because, until the end, they would like to pull off one more good shot.

Frank Horvat : It is true that subjects get used up. The trees that I photographed got used up, I couldn’t indefinitely go back to the same ones. Your bouquet of flowers gets used up under your eyes. Or, rather, your look gets used up on the bouquet. Your awareness gets used up.

Photo Edouard Boubat

Edouard Boubat : Absolutely. There is a word we haven’t used yet: virginity. It is a very beautiful word, though nowadays one makes light of it. But it is very important. To make a photograph, the plate must be virgin, but your eye as well. Some say “innocent. Boubat is an innocent guy.” I am no more innocent than anyone else. When one has been in Africa or in South America or in India, where there were hundreds of thousands of lepers, one cannot remain innocent. I was in an African village and everyone was shaking my hand and from time to time I would realize that they didn’t have fingers. Poor Boubat acted as if he hadn’t noticed. Because he had seen them, poor beings, their difficulty in just standing on their feet, the suffering they endured for a bowl of rice. No, I am not innocent. But, still, one must retain a certain innocence to keep one’s eyes fresh – and I have that innocence. People say, “Oh, good Boubat, brave Boubat, what nice photos he makes!” But my purpose is not to make nice photos, even though sometimes I like to show bouquets of flowers. But what does it mean, showing a bouquet of flowers? It means knowing that, behind that bouquet, there is all the misery of the world. Through that bouquet, the photographer may suggest something that is beyond.

Paris, July 1986

Translation: Charles Martin,

Department of Comparative Literature, Queens College,

City University of New York, September 2003